'The Allegory of Good and Bad Government' (A. Lorenzetti): Why these 700-year-old fresco panels are more relevant than ever (part 1)

How this centuries-old painting helps us understand today's democratic crises.

This is the first part from a series about ‘The Allegory of Good and Bad Government’ by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Part 2 is available here.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Siena was not only Florence's greatest rival but also a significant economic and cultural center. Its artists developed a pre-Renaissance style that had not yet broken away from the International Gothic but was eventually supplanted by Florentine innovations.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290 - 1348) was one of these painters. His masterpiece, The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of fresco panels painted in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, stands as a secular triumph. More importantly, it is a lesson for anyone aspiring to govern one day. No one should place himself or herself above citizens or high moral values. This is something our governments have somehow lost today, which is why this painting is more relevant than ever.

This painting, which is actually three painted walls, is rich in detail and meaning. To avoid the reading indigestion, I will break it down into several parts. Here is the first one, which focuses on the artistic and political context in which Lorenzetti created this magnificent work.

Artistic Heritage: a New Subject and an Immersive Scale

Though this post’s main focus is not on art, understanding the artistic significance of this fresco helps us appreciate its political power and relevance.

The scale of the work is striking. The three panels cover three of the four walls of the Sala dei Nove (“Room of the Nine”), measuring 7.7 x 14.4 meters. The central section is dominated by the Allegory of the Good Government. To the east, its counterpart, Effects of Good Government, and to the west, its opposite, The Allegory and Effects of Bad Government.

Its impressive size makes it the largest secular series of paintings from the Middle Ages. But, ahead of its time, it is also considered the first major political painting of the Renaissance.

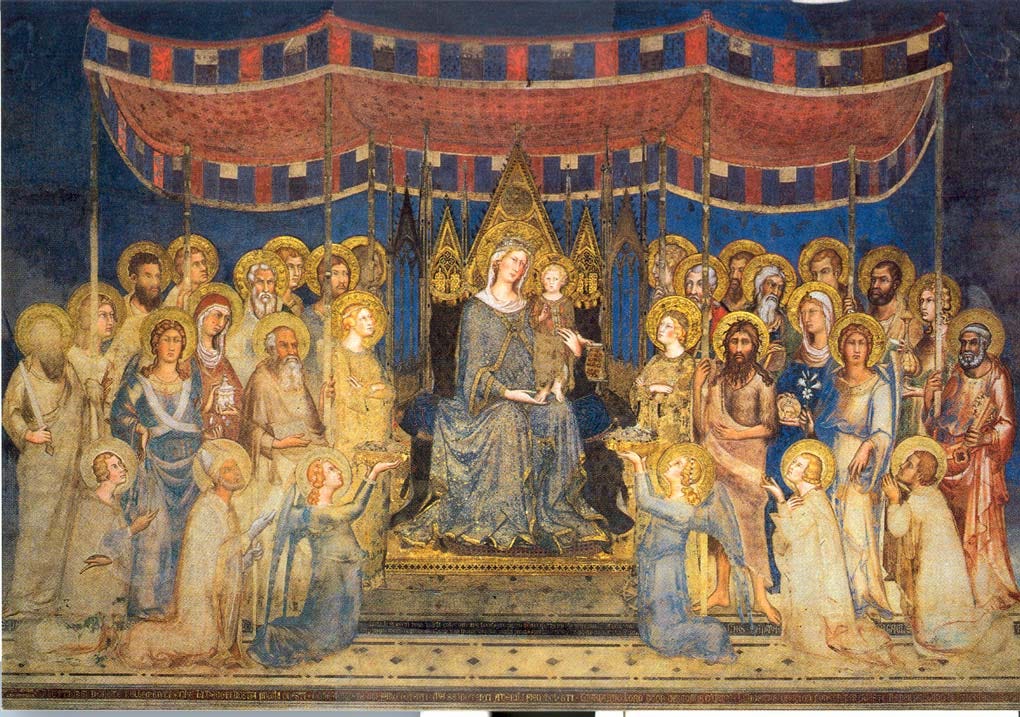

The subject is no longer religious. It is not about which Saint protects the city (see Simone Martini’s ‘Maestà’ below) but rather about allegorical figures reminding rulers that their actions will determine the city's future, for better or worse.

Unlike most art of the period, which was primarily religious, Lorenzetti’s work emphasizes secular governance and civic themes - a groundbreaking development that reinforced the importance of secular rule in Siena’s political structure.

And it is no coincidence that these frescoes were painted in the Council Room.

The Influence of the Frescoes on Siena’s Politics

Siena’s governance was an anomaly in 14th-century Europe, where monarchies dominated. From 1287 to 1355, Siena was a republic governed by the Noveschi (Government of Nine). These officials were selected every two months by a secret assembly of Noveschi and other key figures from various social orders within the city.

To prevent power from remaining in the hands of a few, strict rules were in place: officials could only be re-elected after a significant hiatus, and no two individuals from the same family or company could serve simultaneously. This system was effective - between 3,000 and 4,000 individuals were nominated over the 67 years that this political system existed.

In 1318, a reform modified the process slightly, allowing the municipal council to elect the Nine from a list of nominees. The general administration remained the same though.

The power was given to the citizens, and their representatives were drawn from the middle class, primarily artisans and merchants. The signature of the Nine on official documents gave a clear indication of their purpose: “Governors and defenders of the Commune and the people of Siena”. A revolutionary concept for the time!

Beyond the electoral system, the Nine were subject to strict regulations during their two-month terms. They were required to live in the Palazzo Pubblico, separated from their families, and forbidden from associating with Siena’s wealthiest families to avoid conflicts of interest and corruption.

The Nine gathered in the Sala dei Nove, where Lorenzetti’s frescoes surrounded them. Whenever they debated or made decisions, they faced the Allegory of Good Government on one wall, the Effects of Good Government on another, and The Allegory and Effects of Bad Government on the third. What a powerful reminder to carefully weigh the consequences of every decision!

These frescoes served to remind the Nine that the fate of their city depended on their actions. The paintings reflected Siena’s political environment and encouraged rational thinking, a departure from purely religious beliefs, and entrepreneurship, given that the middle class of Siena was dominated by craftsmen and merchants.

Now that we have the context, we can turn to the central panel, the most important piece from which everything else flows: the Allegory of Good Government. But that will be the subject of next week’s post…