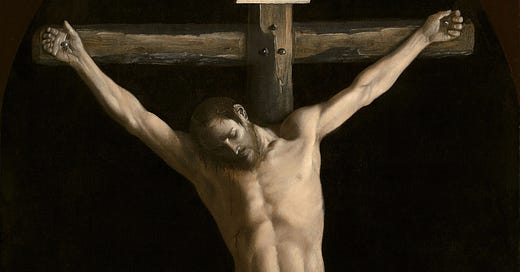

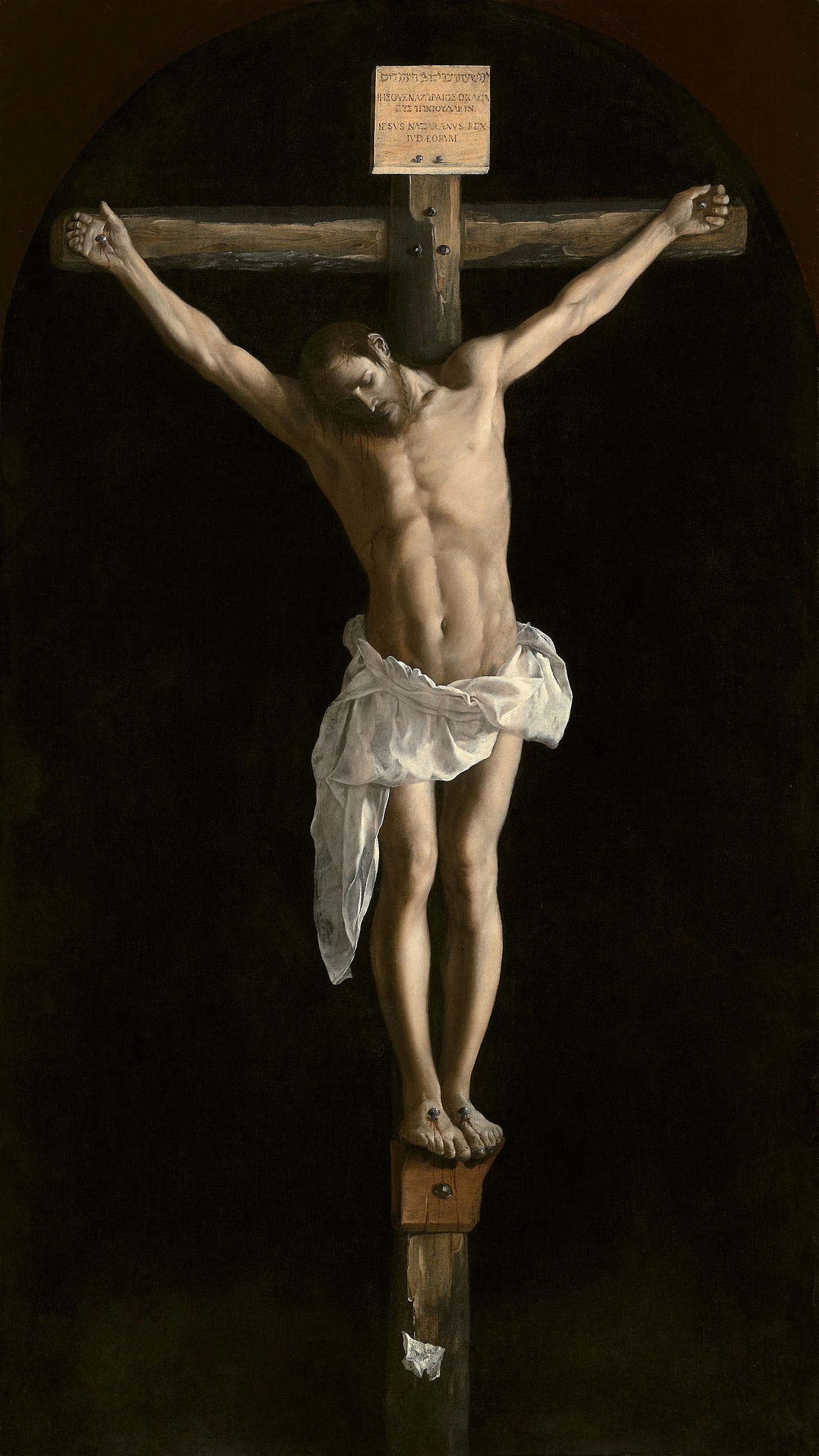

If Zurbaran painted Christ on the cross almost 30 times, his first version, dating from 1627, is certainly the most admirable. Its perfection lies in the simplicity of its subject, with Christ and his cross standing out impressively against a simple black background.

Religion

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) signed a particular contract in 1626 with the Dominican Order in Seville, committing to complete 21 paintings in 8 months. Despite this rigorous pace, Zurbarán created one of his most-well known works, a true Spanish Baroque masterpiece.

This religious purpose likely explains some of the characteristics of ‘The Crucifixion’ . Its size, 290.3 x 165.5 cm, suggests that it was intended as an altarpiece, possibly for a chapel with a light falling from above and to the left.

The painter also adhered to the Counter-Reformation ideals which advocated for representations of Christ alone. Many theologians furthermore thought that the body of Christ could only be perfect by definition, and that is exactly what Zurbarán achieved: a perfect body, magnified by the crude light and the dark background.

‘The Crucifixion’ was admired since it has been painted, especially by the people of Seville, to the extent that the Municipal Council of the city invited Zurbarán to come and settle in the city in 1629.

Tour de Force

What do we see in this painting? Christ is nailed to a cross, nude except for a white stiff linen cloth around his waist, which contrasts dramatically with the black background and the supple lines of his muscles. And that is pretty much all. The perfection of the painting lies in its simplicity and how everything, especially for the time, has been executed perfectly:

The absence of any narrative details creates a direct confrontation for the viewer with Christ’s sacrifice: a key message after the Counter-Reformation. Today, even for non-Christians, it creates a dramatic staging that appeals to the imagination;

The stark chiaroscuro, with Christ’s body emerging from deep darkness, serves as both a religious metaphor and a striking visual impact, magnifying relief and depth of the subject, while focusing the viewer’s attention on the crucified figure;

The sculptural quality of Christ’s body is evident, almost adding one additional dimension to the two-dimensional canvas. The realism of the figure is conveyed by the painter’s understanding of anatomy, and details such as the skin texture or the difference in materials (the iron nails, rough-hewn wood of the cross).

All of these elements contribute to the painting’s emotional power.

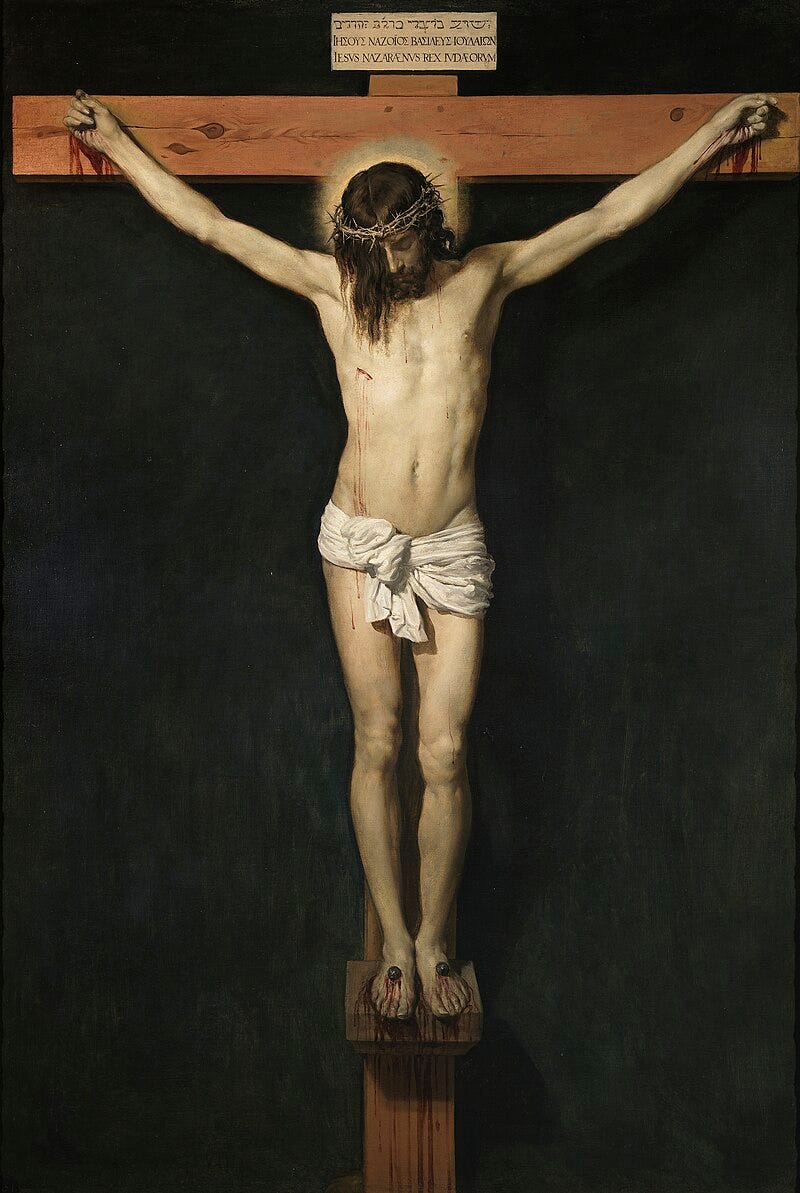

To fully grasp the tour de force of this masterpiece, it can be compared with others having similar characteristics, including the four nails driven into Christ - their number (3 or 4) being a significant debate of the time.

Velázquez painted the same subject, with similar dimensions, four years later. There is no doubt that Velázquez’s work is a great painting, yet it falls short, dramatically speaking, of the emotional impact achieved by Zurbarán, who has been perfect in both composition and execution.

One might almost forget to have a look at the head of Christ, who has his face tilted on his left shoulder. Suffering seems to have been overcome, giving way to a final dream of Resurrection. In this case, a painting that remains alive and relevant today.