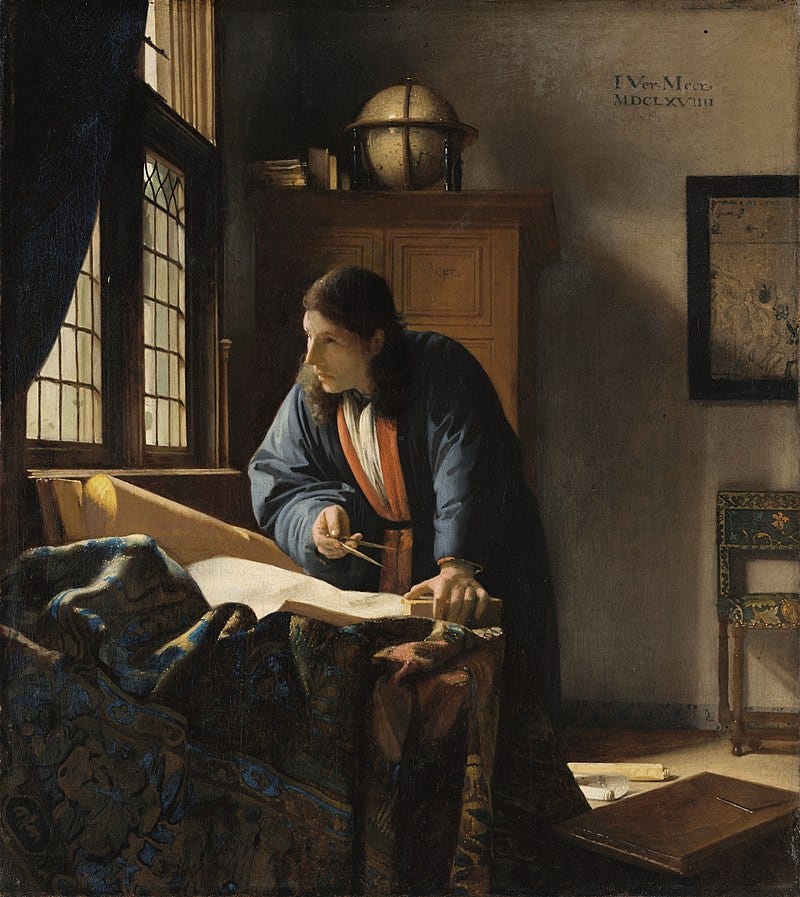

Johannes Vermeer (1632 - 1675) is famous for his genre scenes of characters interrupted in their everyday activities, often in intimate and serene interiors. ‘The Geographer’, along with ‘The Astronomer’, occupy a distinctive place in his works for two reasons:

They represent scientists at work;

They are the only paintings of the Delft masters in which men are the sole subjects.

Subject and Composition

A man, dressed in a Japanese-style robe - the Dutch Republic was the only European commercial partner of Japan - bends over a table with maps and books, holding a pair of dividers in his hand. His gaze is directed out the window, absorbed in his thoughts, as if he has had a flash of inspiration or the need to step away to tconsider his discoveries. The quick “eureka” moment is suggested by the geographer’s face, slightly blurred because of movement.

He stands in a room surrounded by maps, globes and other instruments, reminding him of the current state-of-art in geography and the frontiers science seeks to explore. This is an allegory of the scientific spirit in the pursuit of knowledge, totally immersed in his studies. Nothing can distract him from his task, not even our presence.

By representing a geographer, Vermeer captures the scientific revolution in the society of his time. New territories - not only physical but also intangible, are being explored. Merchants and sailors need maps, and in Netherlands more than anywhere else.

Cartography

Art mimics life, and in the 17th century, life in the Netherlands was all about trade, scientific developments - scientists were attracted by prosperity and the climate of tolerance - and overseas colonization. The Dutch role in the Atlantic slave trade indeed raises questions about the foundations of the so-called “Dutch Golden Age”.

But Vermeer, living with his large family in Delft, was above all a witness to the evolution of the world and its impact on life in his quiet town. Scientific progress provided cheap energy to the Netherlands, from windmills and peat transported through canals. Ships were constructed at a faster pace thanks to wind-powered sawmills.

The Dutch Republic was equipped for worldwide trading and established the Dutch East India Company, one of the world’s first multinationals, to carry out trade activities. Some of the most important trading places for the country were in India or Indonesia and, as a consequence, the production of reliable maps was essential.

Vermeer paid tribute to the latest cartographic advancements thanks to two elements in the background:

The map on the wall is not oriented towards the North but towards the West; we can recognize the Italian peninsula at the bottom. This is not a creation from Vermeer but a very precise rendering of an actual map printed by the cartographer Willem Blaeu in 1625. He was later appointed as the official map-maker of the Dutch East India Company. This kind of maps were used for navigation and here is the full version of this real map:

The globe on the cupboard is oriented to show the Indian ocean, a central place of the Dutch power. This, again, is not an invention from Vermeer but the work of the cartographer Jodocus Hondius the Elder. The terrestrial globe was sold as a pair with a celestial one, which is actually depicted by Vermeer in another of his painting, ‘The Astronomer’.

Relationship to ‘The Astronomer’

The pair of globes is not the only link between Vermeer’s two paintings.

While observing ‘The Astronomer’, we immediately understand the obvious link between the two paintings. The same model with the same type of clothes, the same spatial organization, the same light, the same focus and the same suspended moment in the interruption of the man of science.

This globe is a celestial globe, reminding us the difference in the field of research of the two scientists.

These two globes, made by the same cartographer, were sold altogether. This was also the case for the two Vermeer’s paintings, which were sold as a pair until 1797. However, there is no dialogue between the two paintings, with both men looking to the left, where the light comes from.

In the end, their similarities represent the complementary fields of geography and astronomy and the importance they had for the navigators of the 17th century.

For someone who had almost never traveled outside his city of Delft, Vermeer would probably be amazed by the influence and respectability he has gained worldwide, far beyond the limits known by the geographers of his time.

Same room, different decor.